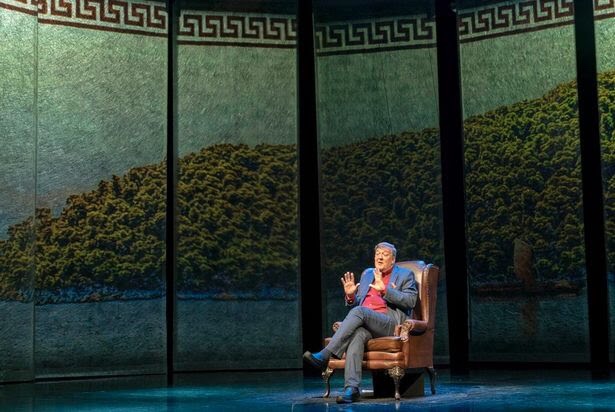

When Nigel Slater released his 2004 autobiography TOAST: The Story of a Boys Hunger, it’s doubtful he ever imagined it would be made into a BBC film let alone become a critically-award winning play which after wowing the West End is now touring the country to packed audiences every night.

Here at Opening Night we were lucky enough to catch up with writer Henry Filloux-Bennett ahead of the shows return to The Lowry to hear a little more about the process of taking the book from page to stage as well as what audiences can expect from this heart-warming adaptation which critics have described as ‘delicious’.

Opening Night: “How did you first become aware of the autobiography and did you read it with the intention of adapting it for the stage?”

Henry Felloux-Bennett: “I was a cook working in London, weirdly in the same hotel that Nigel works in at the end of the book, I was knackered as kitchen hours are stupidly long and I didn’t have any money so I had to live outside of London and commute in. To keep me awake, I would read a book. I was given TOAST one Christmas and it was the first book I picked up as I left one day. I just started reading it on the bus back and forth from the kitchen not only did the story resonate because he has an interesting upbringing and then goes into cooking and I thought – ‘Oh that’s like me’, but also I didn’t have anything to do with theatre but I sort of wanted to do something in theatre, and I thought: ah, that could be the show.”

ON: “Once you’d decided to create the piece was it an instant yes from Nigel?”

HFB: “I tried originally to get the rights for a show in Edinburgh but Nigel said no, thank God because ten years later, the play became much more of a considered thing. Back then, I would have just done it in two hours and hoped for the best. It would have been rubbish so thank God he did say no.”

ON: “Your perseverance clearly paid of as 10 years later Nigel finally gave his backing to the adaptation.”

HFB: “Yes, the Lowry was doing a festival called Week 53 and it was about coming-of-age, Nigel also turned 60 the year it started so I think that had something to do with it. I think also it was something to do with this festival because it wasn’t a big glamorous West End show. We were trying to create this small experience for a very limited number of people that I hoped showed I genuinely wanted to do it. I think a lot of adaptations happen because it’s going to make money – I think he worried about that, not that it would be a big cash cow but that it was cynical. I just thought, oh we can get some foodies to come and see this.”

ON: “What is the starting point when taking a book from page to stage?”

HFB: “I think one of the big challenges of adapting any book to stage is how you a make it interesting to watch. Obviously if you’re reading a book you can be totally absorbed in it. You can enjoy the characters and you can enjoy the plot, but actually when you’re faced with watching something that sort of takes it in a different direction. The challenge with TOAST is that it’s not a narrative-based book, it skips around quite a lot. Finding a journey to go on, from start to finish, was a massive challenge because it doesn’t flow in a linear way. But that’s what made it more fun as well because I didn’t have to stick to normal storytelling rules.”

ON: “Did Nigel have an absolute veto on anything?”

HFB: “Mainly language. There is a bit where they go to Bournemouth on holiday and there is a line about looking out on the sea and the guy who used to play Nigel once said ocean instead of sea. Apparently, that is a massive no-no because Nigel would never have said ocean in the 60s. It’s the details – like making the labels for the damson jam props. He made a lot of props. The general shape of the play he’s always been quite happy with because he understands that you send a book out into the world and it’s up to everyone else how they deal with it”.

ON: “Were you worried about Nigel Slater’s reaction to what you had produced?”

HFB: “I was terrified about Nigel’s response. I think you always think that what you’re doing you quite like but then you have to present it to people who’ve never read it before and you have to present it to the person who it’s about, who wrote the thing itself – that’s terrifying. He was very nice about it. He said he wouldn’t read it until I was happy with it, which was a massive bonus because we didn’t know each other. I might’ve massacred his memoir, which would’ve been awful. Touch wood, I haven’t done that. But he was very generous in saying do whatever you need to do. When I was writing it, I read an interview with Lee Hall, who wrote the screen play for the film. And Lee Hall basically said that you can’t care the person is still alive and you can’t care about the person reading it. You have to write the thing you need to write. If the person hates it you can change it, which he did a little bit, but you have to write the thing that you want to write and don’t worry that there’s a real-life Nigel Slater who will be there at some point. It was great advice, which I followed.”

ON: “Why do you think the tastes and smells are so important in both the autobiography and the play?”

HFB: “If you read the book, which you absolutely should, you’ll know that all the chapters are named after food, like Apple Pie, Marshmallows or Digestive Biscuits. Angel Delight was what I responded to when I read it. Butterscotch Angel Delight is probably the best thing ever invented, it’s an amazing pudding and it takes five minutes to make – who wouldn’t love it? It’s those memories – and the smells. Everyone knows the smell of certain things. If you open a packet of digestives, you know that smell. The same with toast. If you think about it, everyone can tell what toast smells like, just when it’s just starting to burn a little bit. All of those things are in his chapters so we had to respond to that in the play.”

ON: “How involved has Nigel been in the process?”

HFB: “He was literally involved from day one. He was there for the workshop week with The Lowry six months before we made the show and then he was there for every step of the way with the food. I think the tech period for him was the most exciting bit because he works in TV so he’s not used to being involved with how the sets get made. At The Lowry, he made half the props with us. He was literally in the dressing room making labels. I’ve still got the label he made for the Damson Jam bottle, it’s my favourite thing. Oliver, who is the Executive Chef at The Lowry’s Pier Eight, worked very closely with Nigel and James [Thompson], our Food Director, to create things that everyone would get to taste. Nigel came up for tastings and was like ‘this bit needs this’ and ‘it needs a bit more sharpness in the lemon meringue tarts’ so he was really involved.”

ON: “Does any cooking take place on stage?”

HFB: “Yes, I’m not going to tell you what. But there is a scene when we cook on stage. Have you ever seen Billy Elliot? In the script I wanted to copy the bit where he does the angry dance and he can’t express himself any other way. There’s a moment in the play when Nigel gets told something and he doesn’t know how to respond. In my head the only way he could’ve responded was to cook and so it’s meant to be the angry dance for Nigel. It’s a really interesting thing because there is no talking for nearly five minutes. It’s quite intense and Giles had to learn how to cook that dish perfectly. Hopefully it resonates and you’ll find it interesting, but for some people it’s the only bit that I didn’t write and it’s the bit that people cry at. That bit certainly gets people because they can smell and see. The sound of food cooking in a frying pan is amazing, especially in a theatre”.

TOAST returns to The Lowry where it first premiered in 2018 on Monday 11th November for a limited one week run until Saturday 16th November. Tickets available here.

The play was famously seen a very taboo when it first premiered due to the themes and characters, “We’ve come a long way but we still have a long way to go, the cast were told they may have to evacuate the theatre when it was first put on, you’d not have that happen now, that wouldn’t even be entertained today but back then it was. I think we’re getting better well at least I hope we are. Yes back then it was taboo and although not so much now it’s still very, very poignant”.

The play was famously seen a very taboo when it first premiered due to the themes and characters, “We’ve come a long way but we still have a long way to go, the cast were told they may have to evacuate the theatre when it was first put on, you’d not have that happen now, that wouldn’t even be entertained today but back then it was. I think we’re getting better well at least I hope we are. Yes back then it was taboo and although not so much now it’s still very, very poignant”.

📷 David Cooper

📷 David Cooper